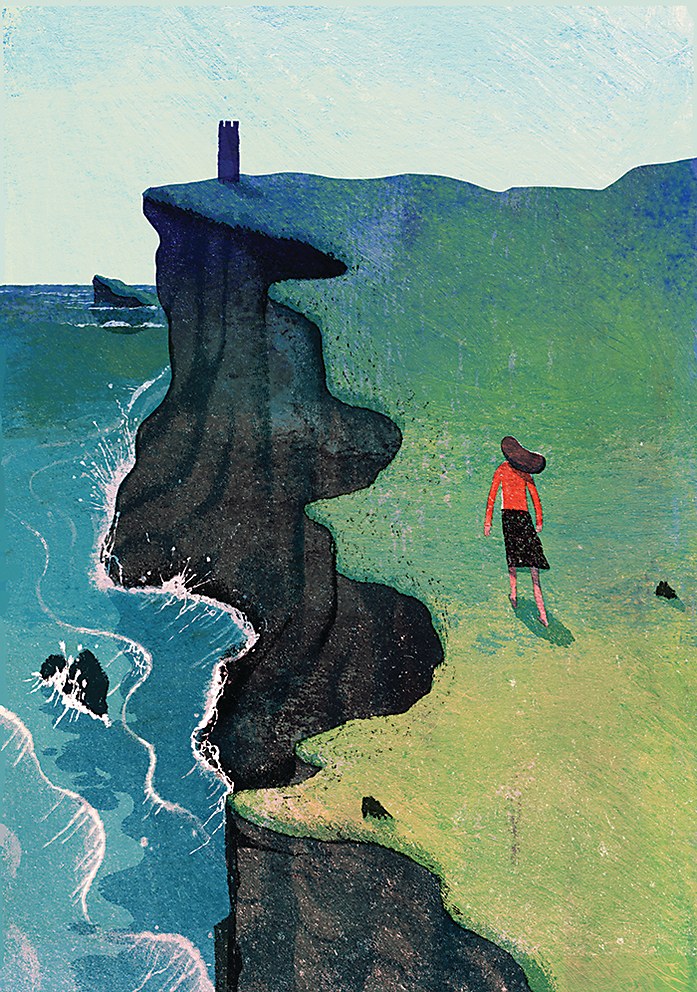

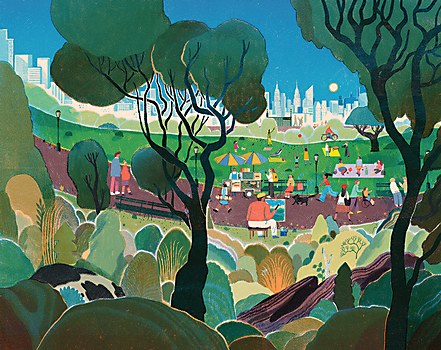

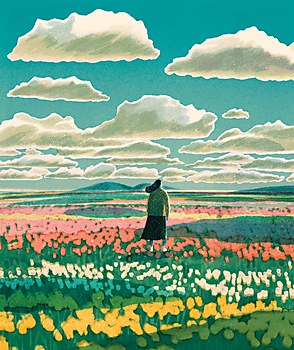

In her illustrations, Lisk Feng has transported readers to arid deserts and lush jungles, the depths of the ocean and the peak of Mount Everest. With an eye for fluid movement and cinematic color, she invites readers into another world, be it the intimacy of a cozy kitchen or the grandeur of the galaxy. And whether she’s illustrating a nonfiction book about the seasons or a New York Times opinion piece about doctors, nature is almost always front and center, either as main character or as metaphor.

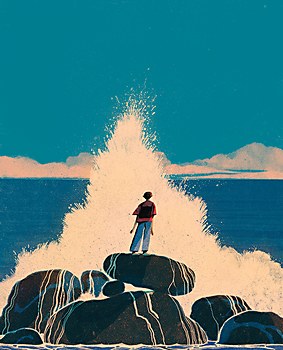

But for Feng, the natural world isn’t just a source of inspiration: as a digital illustrator, it’s also a puzzle to be solved. How to approach the structural complexity of a tree? How to master the reflection of sunlight on water? “I love to look at the things that people feel scared to draw,” she says. Fluidity and reflection, shadow and light—Feng has a way of decoding the complexity of these things, then using her imagination to fill in the gaps with rich, often whimsical details. Whether she’s capturing the force of a waterfall below the surface of a pond or the light in a bead of water running down the shower door, “I try to understand and build a system,” she says. “If I understand water in my own way, then I get to draw water in any form without reference.” The result is work that feels warm and luminous, often tender, and decidedly human.

But for Feng, the natural world isn’t just a source of inspiration: as a digital illustrator, it’s also a puzzle to be solved. How to approach the structural complexity of a tree? How to master the reflection of sunlight on water? “I love to look at the things that people feel scared to draw,” she says. Fluidity and reflection, shadow and light—Feng has a way of decoding the complexity of these things, then using her imagination to fill in the gaps with rich, often whimsical details. Whether she’s capturing the force of a waterfall below the surface of a pond or the light in a bead of water running down the shower door, “I try to understand and build a system,” she says. “If I understand water in my own way, then I get to draw water in any form without reference.” The result is work that feels warm and luminous, often tender, and decidedly human.

That kind of imagery wasn’t in the books Feng grew up with. As a kid, Feng, who grew up in China, mostly read classics like Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. “We didn’t have much of a budget for children’s books when I was young,” she explains. Then, when she was around ten years old, her father—a guitarist in a Chinese rock band—mailed her two sets of manga books, which Feng recalls as “mind-blowing.” A few years later, she stumbled upon Chinese manga magazines and was hooked. “I was like, oh my god, these are fun,” Feng says. Armed with a Wacom Intuos3 drawing tablet, she started creating and sharing her own work online and gained a following early on.

Browse Projects

As a teenager, Feng had agonized over whether to pursue animation, writing or other disciplines—until, that is, the moment she discovered digital illustration. Using a computer to make art was “more fun than any video game I’ve ever played,” she says. “It was addictive. It was the only thing on my mind.” After sitting for China’s notoriously tough college entrance exams, Feng enrolled in the undergraduate illustration program at China Academy of Art, where she had successfully competed with around 800 prospective students for 25 seats. Then, in 2012, she came to the US for an MFA in illustration practice at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Since then, Feng has worked with commercial clients including Apple, Airbnb and Estée Lauder, and editorial clients including the New York Times, The New Yorker, The Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. Then there are the children’s books—more than half a dozen with publishers like Abrams, Enchanted Lion, Flying Eye and Phaidon. The turnarounds are slower, and the process can sometimes be painstaking, but these projects are closest to Feng’s heart: not only is the final published product a piece of pride, but the process itself indulges her curiosity and her love for the natural world.

Nature is Feng’s favorite subject and one she studies closely. When she travels, she finds herself examining the foliage, plants, lights and shadows in a new place. She is easily moved by the quiet beauty of a moss-covered stone or a frozen lake; she meticulously scrutinizes the precise quality of light where a stone emerges from a pond. In the summer of 2016, Feng found herself wanting to draw ice and snow; a few days later, Flying Eye Books approached her about illustrating Everest: Earth’s Incredible Places. The book was a hit, and although illustrating an 88-page book was no easy feat, the process fed Feng’s curiosity—and her appreciation for nonfiction children’s books.

Art director Meagan Bennett first came across Feng’s work at a Society of Illustrators gathering several years ago. “She was so captivating, and her work was stunning,” recalls Bennett, who was working at Phaidon at the time. Later, when it came time to choose an illustrator for the children’s globe-shaped board book Our World by Sue Lowell Gallion, Bennett didn’t hesitate. “Lisk seemed like such an obvious choice for it,” she says, adding that Feng has a knack for capturing movement in a way that feels fluid and organic and for treating color in a way that feels cinematic. “It doesn’t feel unrealistic, but it’s definitively hers.”

Balancing visual information with narrative is a challenge in nonfiction children’s books, Bennett explains: you need to represent the information you’re trying to communicate but provide enough of a visual narrative that it doesn’t feel dry for young readers. “Lisk is really, really good at that,” she says. “She’s really good at capturing these individual narratives on each spread but still tying the narrative thread of the whole book together.”

Our World was such a success that Phaidon decided to build on it with a series. Our Seasons came next, followed by Our Underwater World, which Feng tells me was one of the most challenging books she has ever illustrated. “I’m not afraid of drawing any type of water at this point,” she says.

For the latest book in the series, Feng left the warmth, light and lushness of the Earth behind for the dark void of outer space. Out in fall 2024, Our Universe takes readers out into the far reaches of the galaxy, stopping by Earth’s moon, the volcanoes of Mercury, the International Space Station and the asteroid belt along the way. For an artist whose work is so grounded in nature, going to space might seem like a stretch. It wasn’t.

“Lisk can bring a human element to a silent moonwalk,” says Maya Gartner, associate publisher of children’s books at Phaidon. Feng approached the work like she always does—by developing a “system” with an understanding of how light and shadow look and function in outer space. Then, she put her reference material away and let her imagination fill in the blanks. It’s one reason her work feels so warm and human, even in the vacuum of space. “If you’re drawing realistically and you’ve relied on the reference too much, it will look like a photo—very generic,” says Feng. “When I drew the planet Earth, I obviously needed to look at the photo of the real planet, but I’d stare at it for some time, then put it away and start my own version.”

Feng’s work glows with her deft use of light and shadow. So, a few years ago when Enchanted Lion publisher Claudia Bedrick began looking for an artist to illustrate a new children’s book in which light and shadow were central characters, Feng’s name was on her shortlist. There Was a Shadow, by Bruce Handy, follows a girl from dawn to dusk as the light and shadows around her shift and transform. “The quality of light Lisk is able to render—and within a digital medium—is incredible,” says Bedrick. “And since light and shadow are the main characters in his book, it was going to be incredibly important to have someone who could tackle that problem.”

Illustrating a book about shadows and light presented a whole new set of challenges for Feng to puzzle out. (For starters: On which side of the book would the sun rise?) From there, she not only had to capture the different qualities of light, from the brightness of noon to the muted glow of twilight throughout the day—she also had to be conscious of the shadows’ length and angles as the narrative progressed, as well as shifting the color palette from the honeyed hues of dawn to the muted pinks and purples of dusk.

The result has the organic quality of hand drawing, but Feng did all the work on an iPad, a tool with which she was less familiar than Photoshop, which she uses “like breathing.” That process of discovery yielded a different look and feel in her work. “I find the iPad’s software is a different process, so I see it as a new tool, and my style changes,” says Feng. “This was a perfect experiment for me on iPad, and I could discover this style confidently.” She considers it some of her best work to date.

Though an older generation of artists may see illustration created in Photoshop or Procreate as somehow inferior to, or less “authentic” than, hand drawing, Feng challenges that idea. “To me, these are all the same,” she says. “They are tools. I wouldn’t judge any illustration based on if it’s a digital piece or oil painting or watercolor. It doesn’t matter to me at all.” Nearly all her students in her most recent class at School for Visual Arts, where she teaches, work exclusively on iPads.

In the classroom, Feng isn’t afraid to challenge those long-held beliefs—and in guiding her students toward their own professional careers, she doesn’t attempt to retrofit the old rules onto an evolving industry and a changing world. (She doesn’t, for example, implore her students to assemble a physical portfolio and lug it around to meetings.) Instead, she encourages her students to build supportive communities with their peers—rather than focus entirely on networking with higher-ups—and to explore other potential income streams that might look a little different from how previous generations of illustrators made money, like selling your work on TikTok or Etsy.

She also encourages students to find their own ways to protect their relationship with their art, something Feng herself has struggled with particularly in the wake of the pandemic. Cultivating friendships; taking time to pursue other hobbies outside of drawing (like playing guitar, or knitting tiny hats for collectible dolls, which she sells on Instagram); and keeping a low-stakes, no-rules sketchbook—for Feng, all these things are crucial not just for nurturing creativity, but also for keeping burnout at bay.

Animated and amicable, Feng has an infectious and often very funny energy. Spending time in the classroom, which she has done since 2016, is a way for her to channel that intensity. (“I feel like if this part of my energy doesn’t spread out, I’m gonna die,” she jokes.) But beyond connecting with her students day to day, she also finds it fulfilling to be a part of their artistic journeys as new classes come and go. “I just go and give some suggestions and a little bit of advice, and I can be part of their lives,” says Lisk.

“I’m kind of like the stone in the river. A lot of the water touched my head and then flowed away, and I’m still in the same place. I feel kind of great about that.” ca