When you’re under the influence, time lapses languorously: Your senses thicken. Sweets taste more sumptuous. A heart-shaped patch of light shining through a window seems like the most wonderful thing you’ve ever witnessed. The world abides by the logic of an incoherent dream. It’s difficult to depict these feelings in a single image, but the Los Angeles–based artist Zen Sekizawa managed to capture these sensations in her campaign photographs for the marijuana company Miss Grass. For example, in one picture, a crab claw holds a hibiscus flower engulfed in flames up to a half-burned joint. And in another photo, a peony fondles a lit spliff, the smoke curling seductively above the flower’s petals.

Maren Levinson—Sekizawa’s long-time agent who has coordinated with the artist on many projects like this one—says that “[Sekizawa] worked in a flower shop in high school and studied theater, so she just loves working with flowers. She makes great compositions, and there’s always something a little surprising and disturbing in her work.”

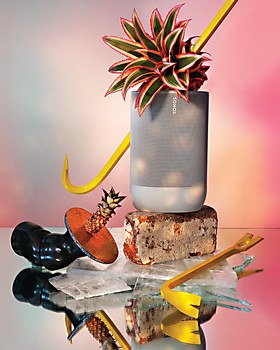

In the Miss Grass campaign and many of her others, Sekizawa upends the everyday, using film and photography to transform ordinary objects—like colorful makeup sponges and satin hair scrunchies—into dream-like tableaux that tell tales about these items’ histories.

“If I had to describe it in one sentence, I would say that Zen’s work communicates artful composition and technical lighting with an underlying punk rock aesthetic,” Levinson says.

Browse Projects

Sekizawa had similar ruminations about her own visual style, describing it as, “a little unsettling, beautiful and striking, but also kind of weird. It’s not your typical beauty product shot, and it’s nice to know that people appreciate that sort of aesthetic.”

Learning how to weave such uncanny visual narratives took time. Sekizawa has been working as a professional photographer, filmmaker, director and fine artist for more than two decades, eventually amassing an impressive roster of clients, including Apple, Google, Netflix and Sephora. But her advertising portfolio only encapsulates a sliver of her inventiveness. The multidisciplinary creator has a dynamic practice that incorporates everything from a furniture and design collective called Mano Ya (mano-ya.com)—which she cofounded with her partner, the painter Mario Correa—to community organizing with local groups like J Town Action and Solidarity to her fine art photography, some of which was published in a book called You and I See Why, released by Hesse Press in 2014.

“It’s hard to pigeonhole her because there are a lot of things she’s very good at,” Levinson says. “She started in music and fashion. She has a pretty punk rock aesthetic because she grew up in that environment in Los Angeles in the 1980s, so it comes to her naturally.”

Indeed, Sekizawa’s upbringing in Los Angeles is a central aspect of her biography; the artist is a fourth-generation Japanese American and a second-generation Angeleno, so her ties to California run deep. Now, Sekizawa goes to great lengths to protect the community that she grew up in, and in the past, Sekizawa has done work with organizations like We the Unhoused, which helps Angelenos without homes, and China-town Community for Equitable Development, which ensures that affordable housing and community-focused businesses have a place in the historic neighborhood.

“Unfortunately, gentrification, hyperdevelopment and displacement are quickly erasing the diverse culture I love so much about Los Angeles, and I feel an urgent responsibility to try to preserve it,” Sekizawa says in an interview with OseiDuro, a fashion company based in Ghana. “I miss the days when people from San Francisco and New York didn’t like coming here.”

Back in those days—the 1980s and the 1990s—Sekizawa was just a child. The environment of her youth permeated her early work when the photographer began to create images of her surroundings. “I definitely didn’t start with sketching—I can’t draw,” she says. “When I was five, my grandfather gave me a demo with a Polaroid camera. We would go on fishing trips, and I would blow through a bunch of Polaroid film.”

Sekizawa’s inclination toward imagination runs in her blood—her family is filled with people who have ties to music, food and visual media. As an adolescent, Sekizawa was surrounded by these relatives, many of whom encouraged her to explore her creative pursuits. And Sekizawa’s mother, Nancy Sekizawa, is one testament to her aesthetic lineage: Nancy is a musician who performs with a noted Asian American jazz band called Hiroshima. On the other hand, Zen Sekizawa’s maternal grandparents were more inclined toward the culinary arts. In 1946, they started a Japanese American restaurant in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles and served dishes like chashu ramen—ramen with pork—and fried rice to local residents. Eventually, Nancy took over the establishment and rechristened it as the “Atomic Cafe”, turning it into “a punk haven frequented by the likes of Devo, Blondie, Sid Vicious, X and David Bowie,” as Mark McNeill wrote for public radio station KPCC’s culture show Off-Ramp in 2016.

“You know, I didn’t really want [Zen] to be with a babysitter all the time,” Nancy Sekizawa said in an interview with the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. “She stayed with me, and we made like this little bed in the back of the restaurant on top of the dish towels. We made a little cot for [her] that was next to the cigarette machine.”

Sekizawa absorbed this free-spirited energy, gravitating toward the rebellious artists and musicians who frequented the eatery. (According to the Off-Ramp article, Nancy once kicked Andy Warhol out of the cafe and got into food fights with Sid Vicious.) None of this was lost on her, and she began to build her own creative social circles as an adolescent. In the Osei-Duro interview, Sekizawa says that she “just wanted to listen to gangster rap and hang out with skaters at the Beverly Center” when she was a teenager. During this time, she continued to explore the different worlds she inhabited by using her camera lens, snapping pictures of her everyday life. Although her photography started out as a mere pastime, it began to blossom into something bigger.

“I’ve always loved photography, but I only thought of it as a hobby in high school,” Sekizawa says. “I would ditch all my classes and hang out in the dark room.”

Eventually, Sekizawa decided that she wanted to attend art school, and in college, she further honed her craft by taking classes in photography and advertising. As she continued to make pictures and videos, Sekizawa looked to music videos for inspiration. “I think they were a big influence on me,” she says, “growing up in the ’80s and ’90s in such a musical environment around the time of the birth of music videos.”

After earning her BFA in photography from ArtCenter College of Design in 1999, Sekizawa carved out a multifaceted career for herself. Once she graduated, she began working as a photographer for a production company and developed an interest in motion theory, which ultimately led her to take night classes in filmmaking. As she sharpened her skills in photography and video, Sekizawa was able to cultivate a career in both fine art and advertising. In the latter, she has partnered with clients such as Corona, eBay, shoe brand Jimmy Choo, Modelo, Playboy, Sony, The New Yorker, T-Mobile and WIRED.

“I think my whole career has been trying to find a really good balance between advertising work and artistic work,” Sekizawa says. “I want to see how far I can blend those two worlds.”

Some pieces from her oeuvre speak to the creator’s dynamic nature and bridge the gap between commercial and fine art. For example, in 2010, Sekizawa shot a series of short films for the shoe designer LD Tuttle. One of the videos shows Emilie Livingstone, a former Olympic rhythmic gymnast, wearing black shoes outfitted with wedge heels. Livingstone moves her body sinuously, going through a series of handstands, crouched positions and back arches while wearing the footwear. There’s something uncanny about this piece—the lighting is dim, ambient music by Aaron Hemphill punctuates Livingstone’s movements and the gymnast wears a mask that completely obscures her face, all making the video feel more like a slow-moving fine art film than a brightly lit advertising campaign.

“I think that sort of work aligns with my still life work right now because it feels a little bit surreal and strange,” Sekizawa says.

These lively outlays do, in fact, feel surreal. When you look at one of Sekizawa’s still lifes, it feels like you’re taking a trip through the northern lights—these photos are awash with electric hues of fluorescent fuchsia, Pyrrole orange and pungent pink. This certainly rings true in Sekizawa’s campaign for the cosmetic company Beauty Blender: one of the pictures shows a makeup sponge set against a backdrop of electric-blue circles, glowing palm leaves and open orchids. The vibrant combinations of colors and lighting are a testament to Sekizawa’s attention to detail.

“People don’t know how technical she really is,” Levinson states when describing Sekizawa’s process. “Her lighting setup looks like a madman's science project—there are a million clamps and riggings and crazy things. It’s because she started out as a lifestyle photographer where people just naturally light everything. Some people don’t really know how to light, but Zen does.”

Many of Sekizawa’s other campaigns, like her videos for Play! by Sephora and her photographs for Jimmy Choo, also speak to this meticulousness. Her shots are carefully composed; when you look at her flat lays of makeup brushes or high-heeled shoes, it seems like every object belongs in the frame. In a world where many photographers rise to prominence on social media by snapping artful iPhone shots, Sekizawa’s technical virtuosity sets her images apart from the others.

“She thinks about all the details,” Levinson says. “The lighting is really tight, and she has great taste—as most artists do. She’s always looking for ways to make it interesting to her, which, of course, makes it interesting [in the] commercial landscape. But when she follows her taste and what she’s attracted to, it lends itself to great imagery.” ca